The upcoming reduction in net asset purchases is likely to put upward pressure on Treasury yields, but only moderately as rate hikes aren’t yet in sight. Credit and equity markets should be able to cope.

- The forthcoming announcement that the Fed will scale back its asset-buying programme should translate into higher Treasury yields. But, as long as the central bank makes clear that rate hikes aren’t around the corner (our base case), any selloff should be limited to 10–30 bps for 10-year yields over the one to two months following any tapering announcement.

- While overreactions are certainly possible given the starting point, our baseline is built around the lower end of the range. Looking back to 2013, we find that many of the features underlying the taper tantrum are either absent or sufficiently different this time around, suggesting that the magnitude of yield moves is likely to be smaller.

- Equity and credit markets should be able to withstand a moderate rise in Treasury yields if the economic fundamentals – Covid-19 aside – remain relatively positive despite some moderation in growth, and monetary policy stays supportive (even if the stimulus gets reduced). Taking the high yield market as an example, spreads shouldn’t widen significantly, although volatility may rise.

Each August, the main event for markets is the US Federal Reserve (Fed) Chair’s speech at the Jackson Hole Symposium. The challenge the Fed now faces is withdrawing stimulus at a pace that’s neither too late to inflate imbalances nor too soon to excessively tighten financial conditions relative to the state of the economy. Investors have been waiting for weeks to scrutinise Jerome Powell’s words to determine what the Fed’s actions may be and how this could impact their portfolios. Powell suggested that tapering is forthcoming by saying: “At the FOMC’s recent July meeting, I was of the view, as were most participants, that if the economy evolved broadly as anticipated, it could be appropriate to start reducing the pace of asset purchases this year.”

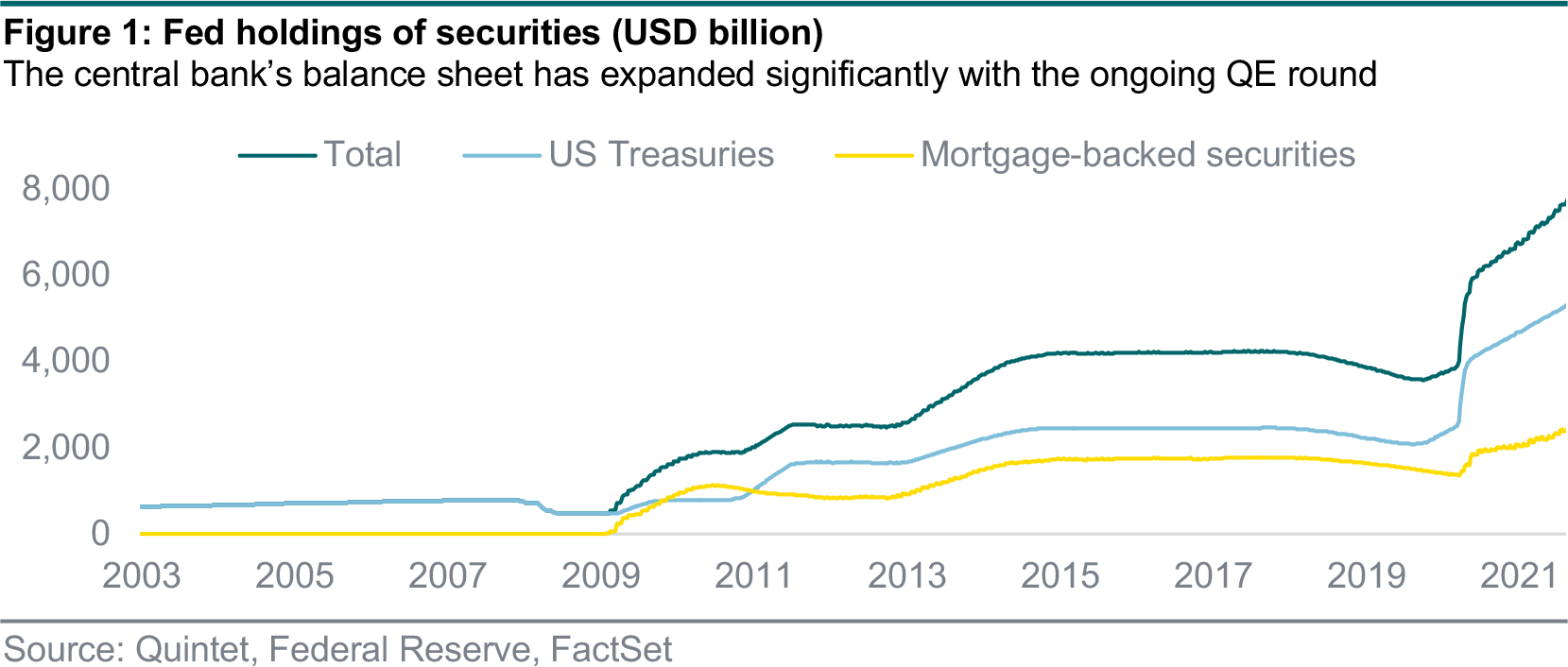

The Fed seems to believe that it has now met one of two goals it wants to achieve before reducing its support (inflation) and is making “clear progress” on the other (maximum employment). The latest payroll miss is unlikely to have shifted this view too much. So, to us, scaling back the bond- buying programme looks warranted (figure 1). A reduction in asset purchases isn’t a change in interest rate policy: “The timing and pace of the coming reduction in asset purchases will not be intended to carry a direct signal regarding the timing of interest rate lift-off, for which we have articulated a different and substantially more stringent test”. What’s the likely impact on Treasury yields? Will credit markets (and riskier markets such as equity) be able to cope? Here’s our take.

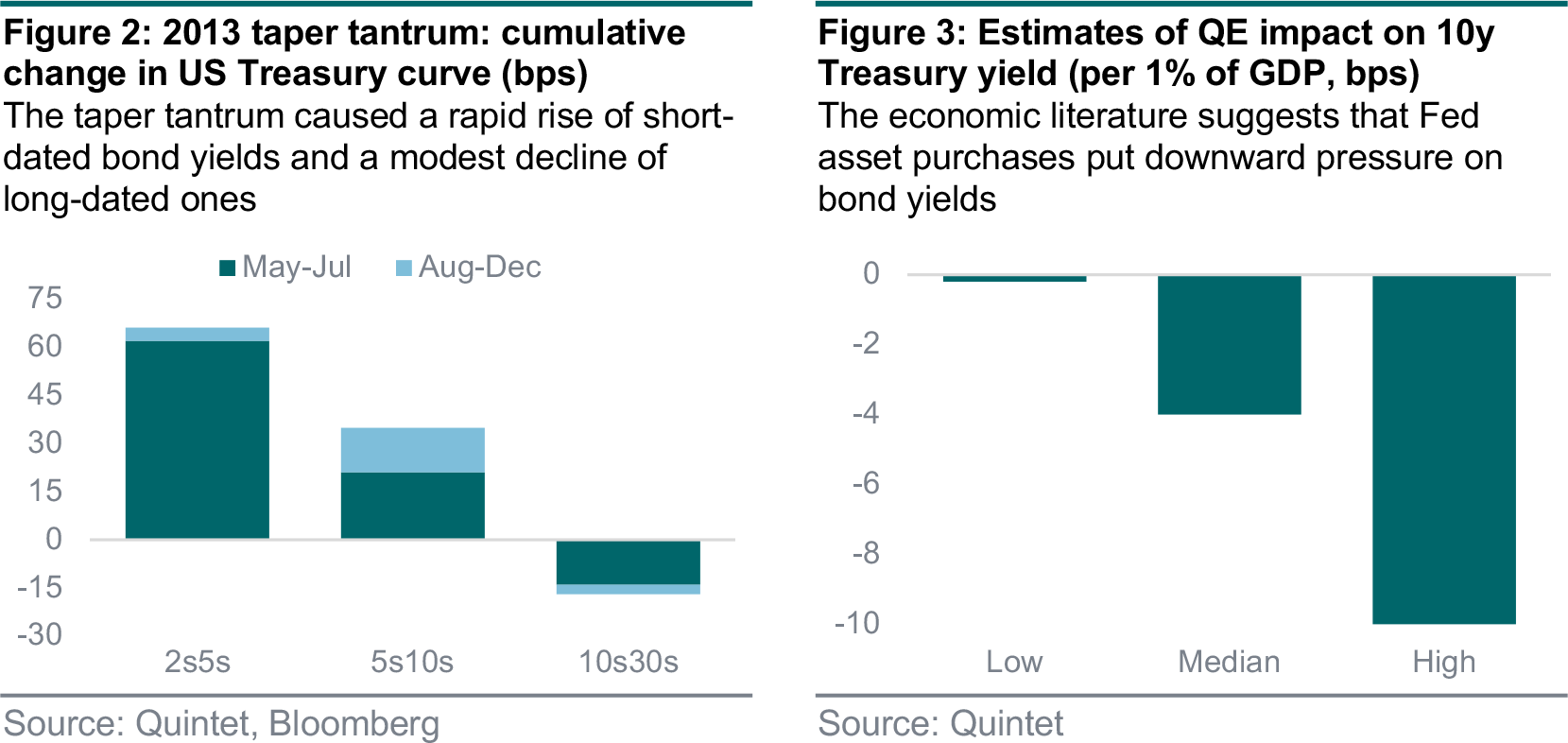

One area where we expect somewhat similar behaviour to the 2013 taper episode is the shape of the yield curve (figure 2). During the taper tantrum, it steepened significantly, first led by the 2s5s curve from May through July, and then by the 5s10s curve (the 10s30s curve flattened modestly). However, the magnitude of any steepening is likely to be materially smaller than in the 2013 episode. The literature points to wider-ranging impacts but, typically, a 1 percentage point (pp) increase in asset purchases as a proportion of GDP translates into about 4 bps of downward pressure on Treasury yields (figure 3) – of which 1–2 bps occur via the risk-premia component and about 2–3 bps via the expectations component – and a 1 pp fiscal deficit increase as a share of GDP translates into about 2–4 bps of upward pressure.

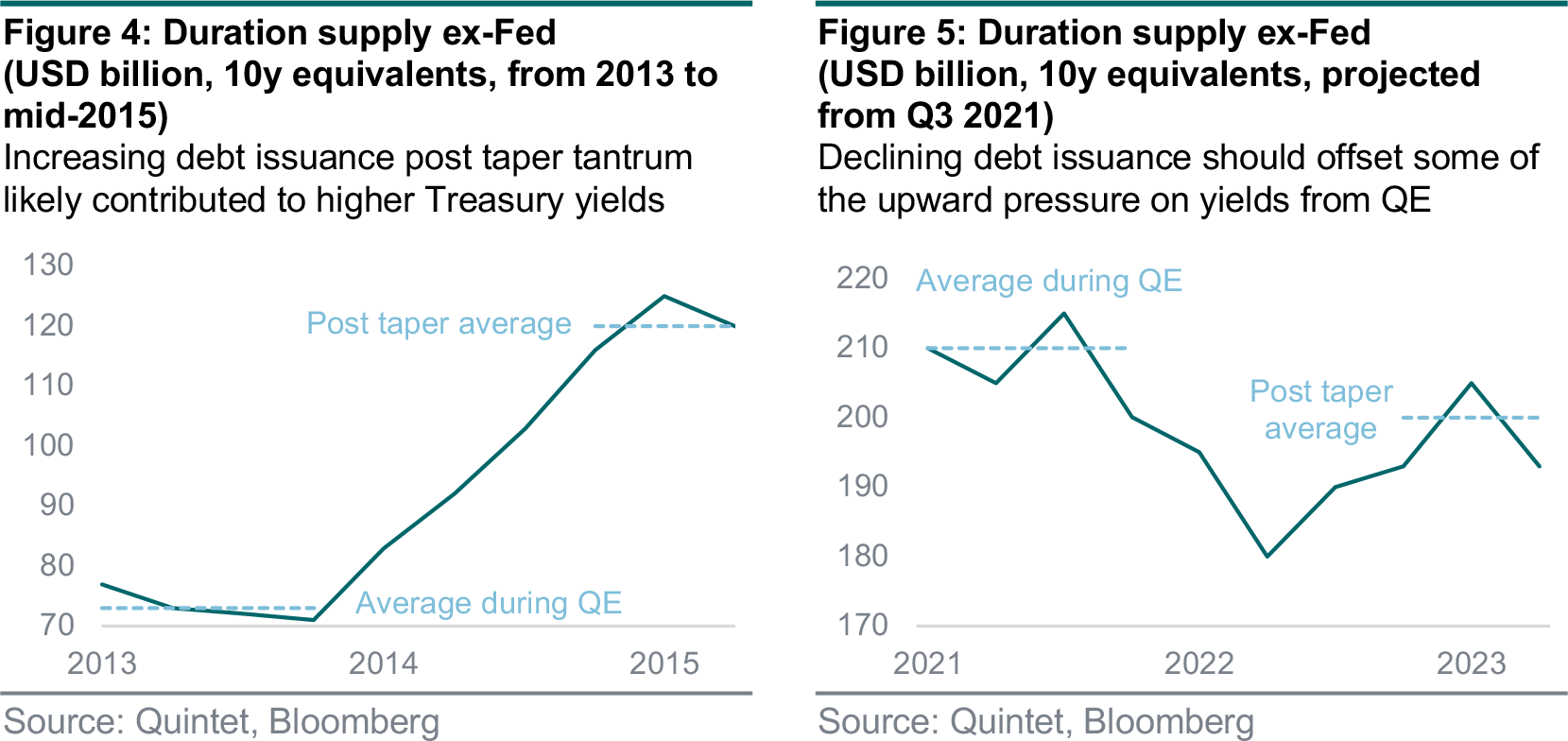

Duration supply available to the public is an important factor affecting bond yields. Today’s issuance backdrop is very different from the taper tantrum (figure 4). Back in 2013, the end of QE mattered much more from a supply perspective: the average monthly duration supply increased by 60% (roughly USD 50 billion in 10y equivalents) following the end of Fed bond purchases. Our survey of estimates suggests that the anticipated increase raised 10y Treasury yields by anywhere from 30 to 50 bps during the taper tantrum. But it’s unlikely to do so this time around. Our expectation for reductions in auction sizes suggests that an end of Treasury purchases would result in a 5% decline (about USD 10 billion in 10y equivalents) in monthly duration supply even as the Fed tapers (figure 5).

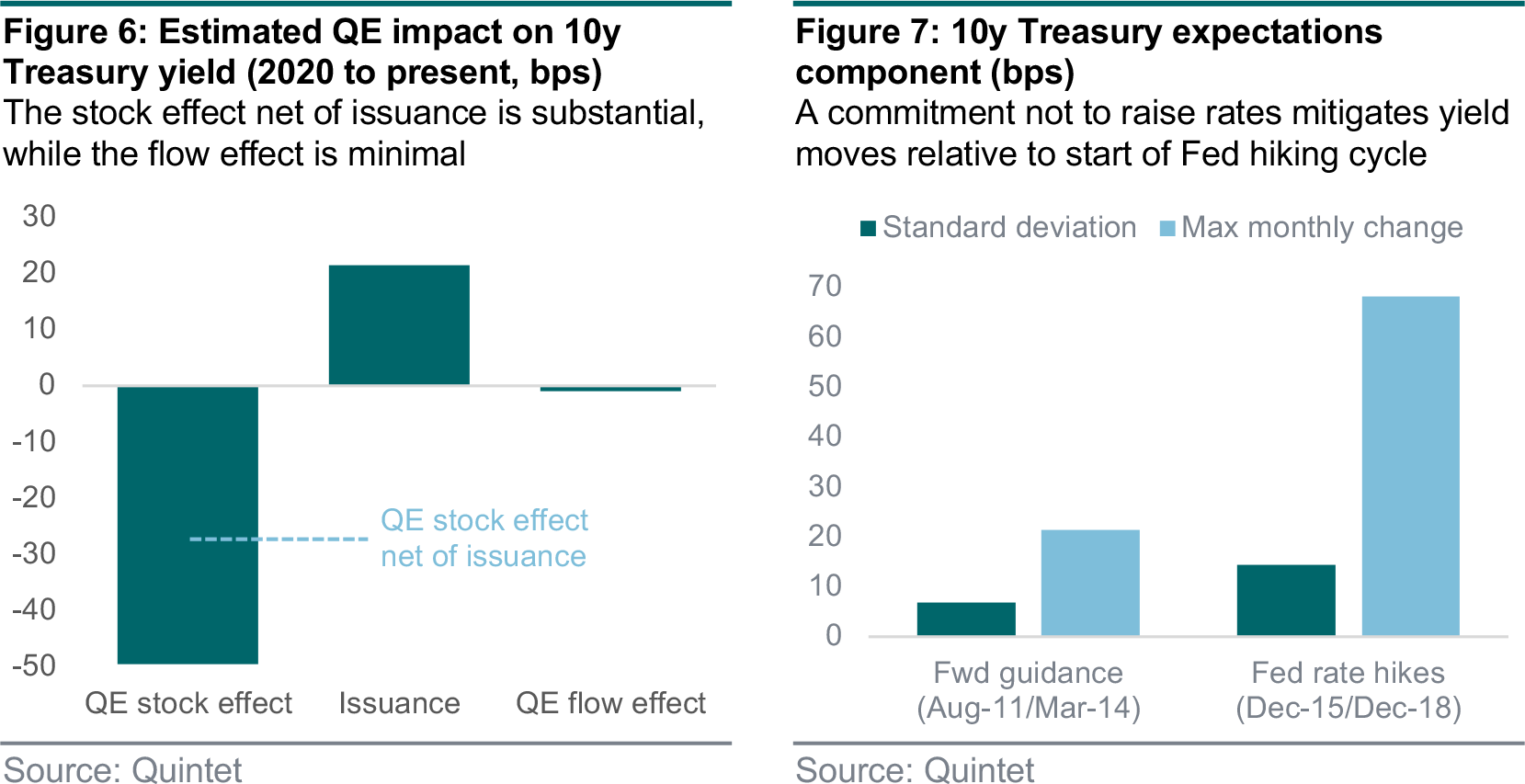

Asset purchases affect yields through both a stock and a flow effect. Our assumptions and survey of econometric studies suggest that, mechanically, the ongoing episode of QE has reduced Treasury yields by some 50 bps at the 10y point via the stock effect – partly offset via higher debt issuance (figure 6). The impact of the flow effect looks negligible. The Fed’s ability to differentiate between tapering its asset purchases and starting to hike interest rates can amplify or mitigate the impact of any taper. The standard deviation and maximum of one-month changes in the 10y expectations component during the last period of forward guidance (August 2011 to March 2014) were both significantly smaller than when the Fed was actively raising rates from late December 2015 (figure 7).

As an illustration, we consider three scenarios where we vary the start of the reduction in asset purchases and its pace (and use our projections for debt issuance, which we expect to slow). The most aggressive, though less likely, taper process – starting at the beginning of Q4 this year and taking six meetings to complete – would result in a reduction in the stock of purchases of about USD 370 billion. This would translate into an almost 8 bps impact on yields (figure 8). While yield moves on any taper announcement are likely to be contained, the risk is that – given that the current level of yields is ‘rich’ – the market response turns out to be disproportionate. Another risk, also pointing to higher yields, is if the Fed forecast (to add 2024 in September) shows more rate hikes than expected.

There are plenty of reasons to see the glass half full rather than half empty. In our view, there’s no specific argument leading to a huge selloff in the credit market. But, even if we don’t expect credit spreads to widen substantially, we expect much more volatility ahead. Moreover, despite positive fundamentals and technical factors, spreads have very limited potential for further tightening as well. We should be in a range-bound period until the end of the year, with relatively resilient high yield markets.

Tapering doesn’t mean ending central bank support. Rather, it’s the gradual slowing in the pace of large-scale asset purchases. This means the Fed is likely to continue to buy (via reinvestment) and support the economy. In contrast to 2013, when Bernanke (then Fed Chair) gave the first signal that a taper was forthcoming, the Fed has been preparing markets with frequent and more targeted communication to avoid a taper tantrum.

Corporate balance sheets have improved. Companies issuing US high yield debt have reduced leverage much more impressively than those issuing investment grade debt, despite experiencing a much larger decline in EBITDA (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortisation) during the Covid-19 crisis and similar EBITDA growth since. Most investment grade companies have decreased net leverage due to relatively high cash levels, but it’s too early to exactly know what they will do with their large cash positions – especially if potentially attractive M&A opportunities were to emerge.

High yield companies’ EBITDA fell dramatically in the third quarter of 2020, while the fall in investment grade came the next quarter. However, credit markets have been quite resilient, partly thanks to the stimulus measures put in place by the US government, so the impact of the declines in both revenues and EBITDA turned out to be quite manageable (given the circumstances).

Additionally, the pain was relatively short-lived: during the first quarter of 2021, EBITDA growth rebounded. That volatility is rather normal in the high yield segment, which is smaller, less diversified, and often with a high weight in cyclical sectors – implying a lower rating.

One reason for this trend is the evolution of the US high yield universe. Following the defaults of the past year or so, quite a few of the most highly leveraged names have been removed while, at the same time, more than USD 260 billion of ‘fallen angel’ paper has increased the overall quality of the index. The global corporate default rate has now returned to pre-pandemic levels. And the number of corporate defaults remains low this year, reflecting strong economic activity and abundant market liquidity (figure 9). We expect this trend to continue over the coming months, likely resulting in ultra- low default rates.

It’s not only fundamentals that are supporting the market – some technical factors are too. Issuance levels are robust for investment grade credit and at record-high levels for high yield. Issuers have anticipated that the Fed may taper its asset purchases, and so they have frontloaded their issuance plans, leading to lower supply for the rest of the year.

The Fed’s bond-buying programme is quite different from the ECB’s, which bought a large part of the market as well but not as much as the Fed – which opened the door to high yield ETFs and fallen angels. The Fed also had the benefit of an ‘announcement effect’ rather than just purchasing actively in the broad market.

Of course, valuations are tight for both markets, but we don’t expect a huge selloff as long as our macro scenario stays constructive. For us, the main driver of much higher spreads isn’t tapering, but renewed and long-lasting lockdowns in key countries, inflation fears, trade tensions and geopolitical instability. Even though we incorporate some of these factors into our baseline, they remain tail risks.

Authors:

Daniele Antonucci Chief Economist & Macro Strategist

Lionel Balle Head of Fixed Income Strategy

Philip Odum Macro Strategist

Bill Street Group Chief Investment Officer

This document has been prepared by Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. The statements and views expressed in this document – based upon information from sources believed to be reliable – are those of Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. as of 6 September 2021, and are subject to change. This document is of a general nature and does not constitute legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. All investors should keep in mind that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that the value of investments may go up or down. Changes in exchange rates may also cause the value of underlying investments to go up or down.

Copyright © Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. 2021. All rights reserved.