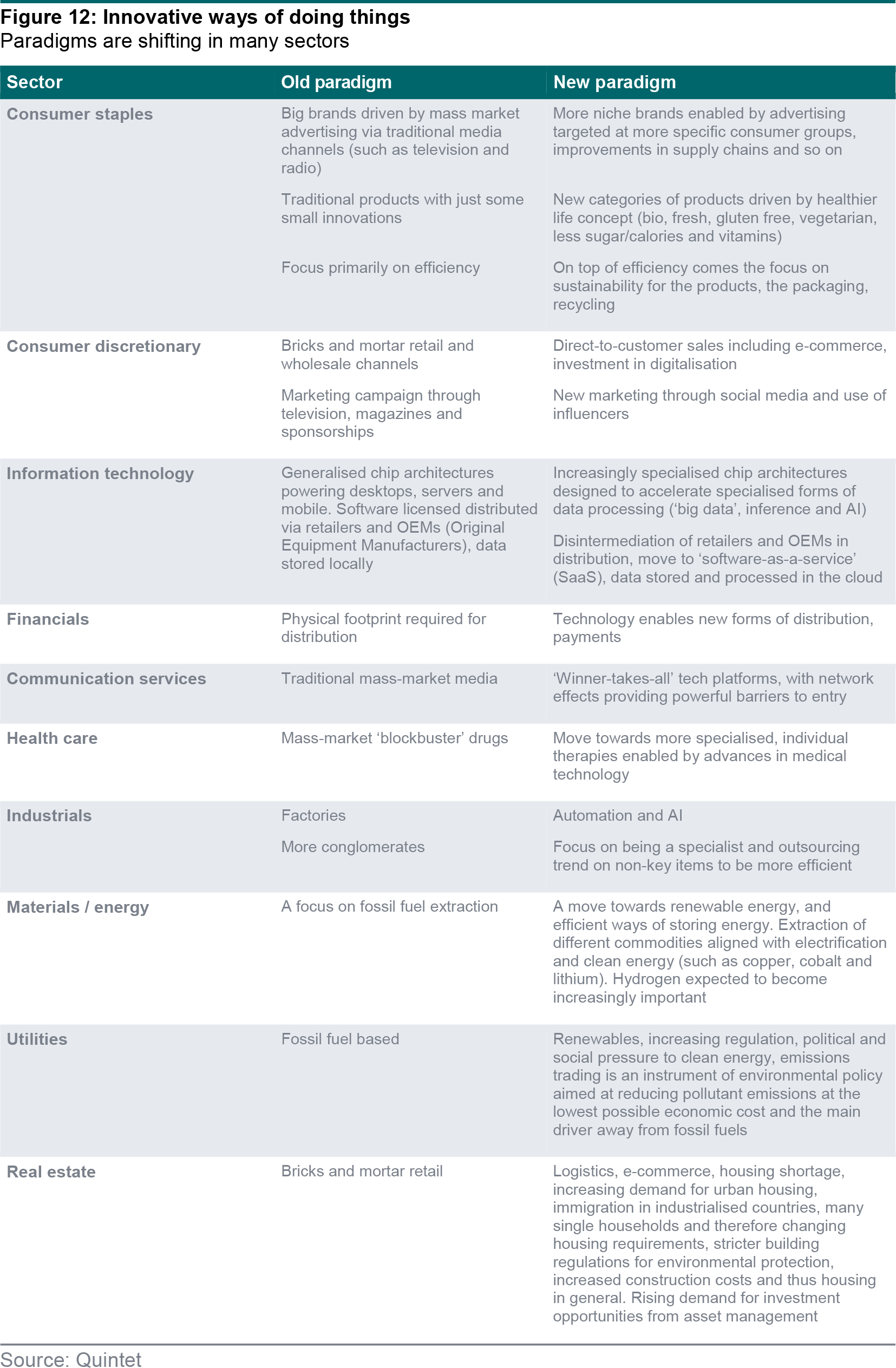

The pandemic has turbocharged a range of pre-existing trends that are changing the way of doing things across many economies. While quantifying the macro impact is highly uncertain, these shifting paradigms are already visible at the sector level.

- Three key structural trends are gaining momentum, partly boosted by the behavioural response to Covid-19. First, a pickup in spending on research and development (R&D). Second, rising capital expenditure on intellectual property products and, eventually, non- residential physical infrastructure (often with a ‘green’ twist). Third, faster spreading of innovation across countries and industries.

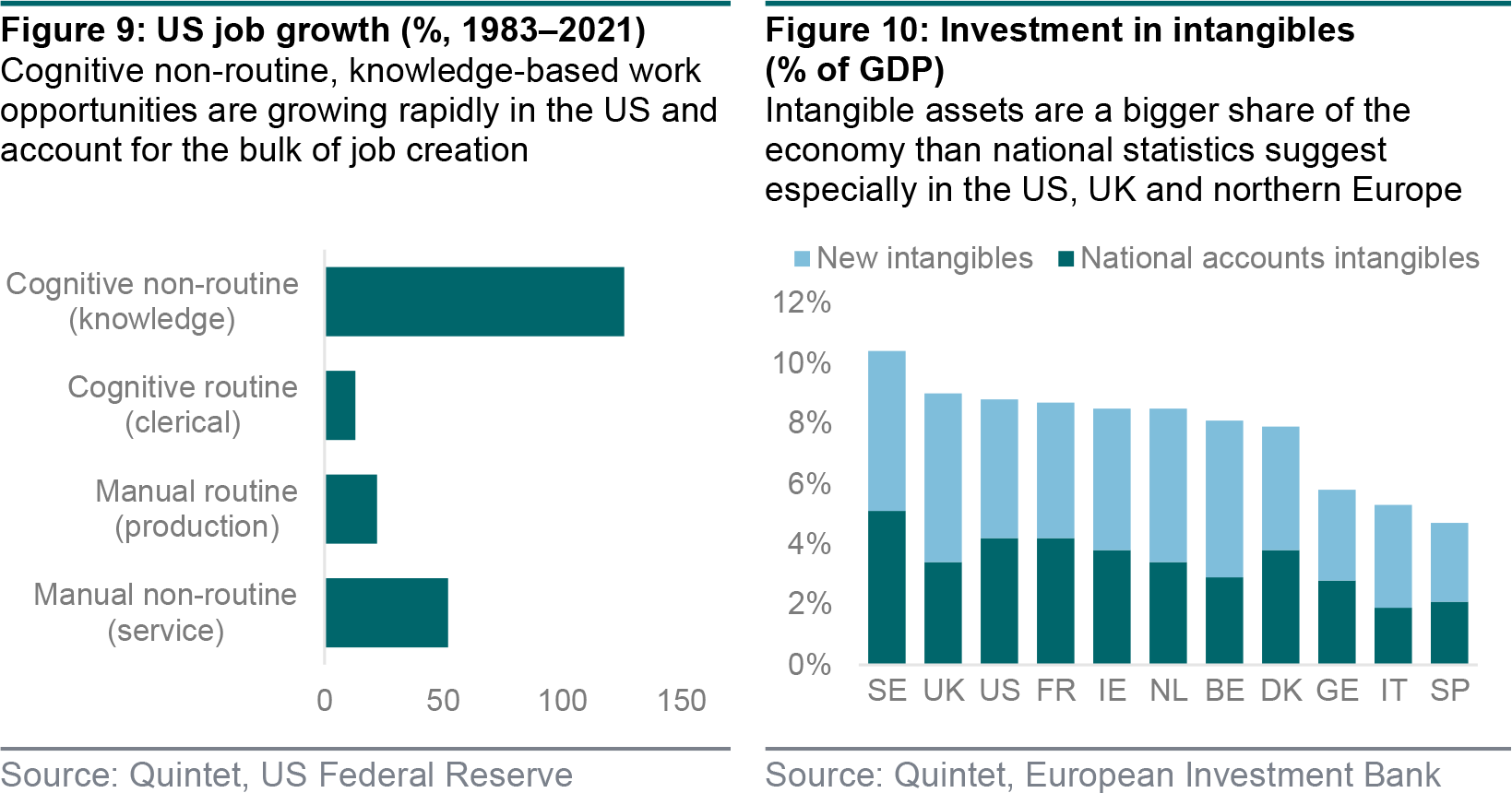

- The confluence of these trends has the potential to at least begin to reverse the productivity decline of the past few years, especially in the US, and to accelerate automation and digitalisation around the world. These trends could also continue to boost job creation for non-routine cognitive roles and tasks, mainly in knowledge-based companies.

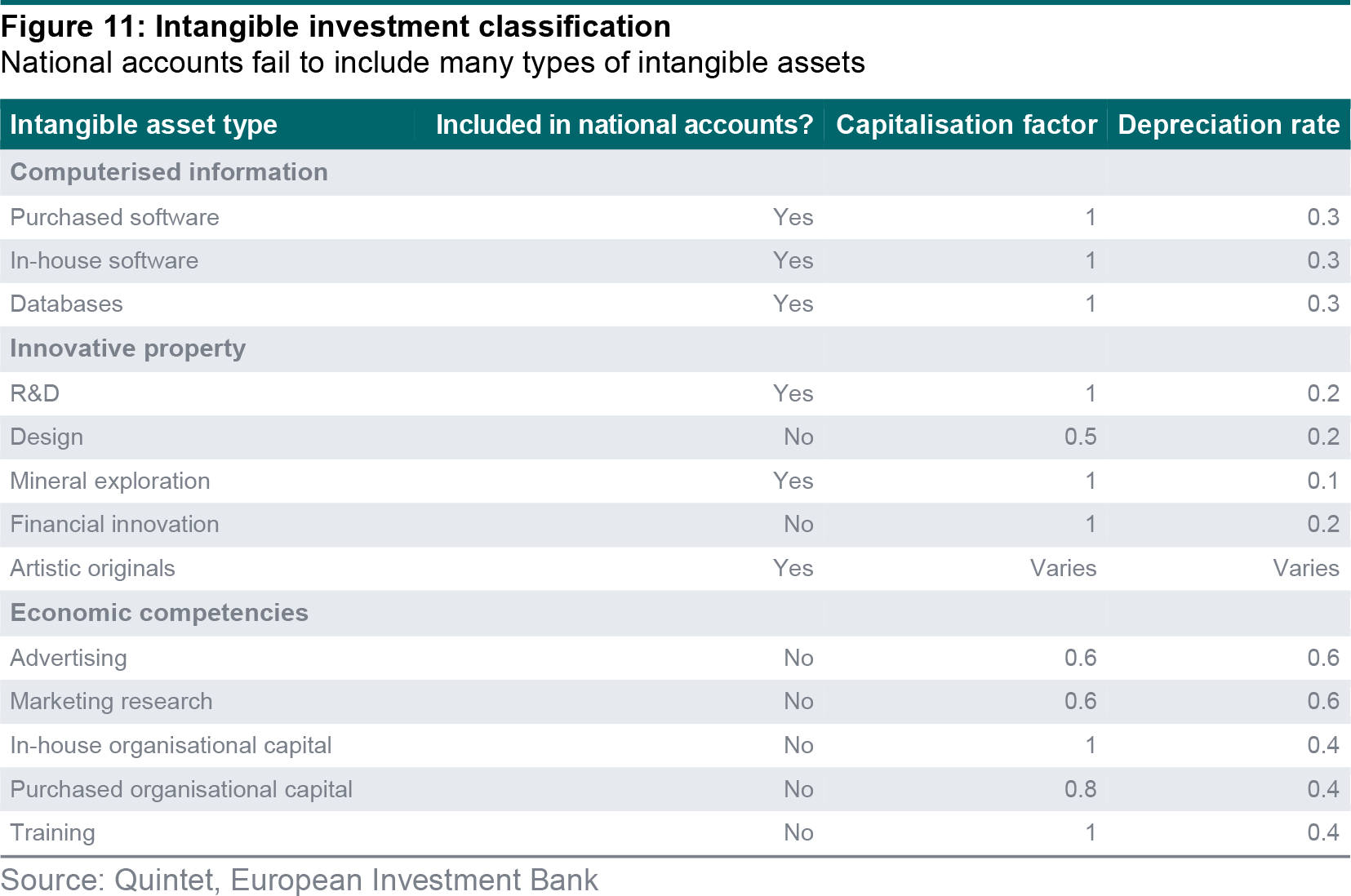

- Much of what’s happening has to do with the rising importance of intangible assets. Some are included in the macro statistics, such as software, data, R&D and content. Many others aren’t, such as brands, marketing, design, organisational and financial innovation, and networks. They are particularly important for the US, UK and northern Europe.

- An asset’s intrinsic value comes from the firm’s earnings power. Valuation approaches relying mainly on company accounts treat many intangibles like ‘expenses’. But if these intangibles can generate future cash flows, and are what makes companies what they are in the eyes of their customers, then earnings and book value may both be understated.

This piece isn’t about stockpicking. Neither is it about sector valuation. Rather, this piece is about disruption. Three key trends, while in motion for some time, are accelerating – and they’re important for single-name securities, entire industries and the global economy. They have to do with rising R&D spending, an increase in capital expenditure on intellectual property products, intangible assets and – given US President Joe Biden’s plans – non-residential physical infrastructure (with a sustainability push), and more and more innovative ways to produce and consume.

What these trends have in common is that they’re driven by technological innovation and, more broadly, the generation and diffusion of new ideas. Measuring the degree of innovation and the impact of ideas is more art than science. Some key macro variables really are unobservable. Have you ever touched and seen things like potential output or total factor productivity? Although quantification at the aggregate level may still escape investors, from certain structural shifts at the micro, sector level it’s possible to use data and intuition to identify these trends as those reshaping economies and markets.

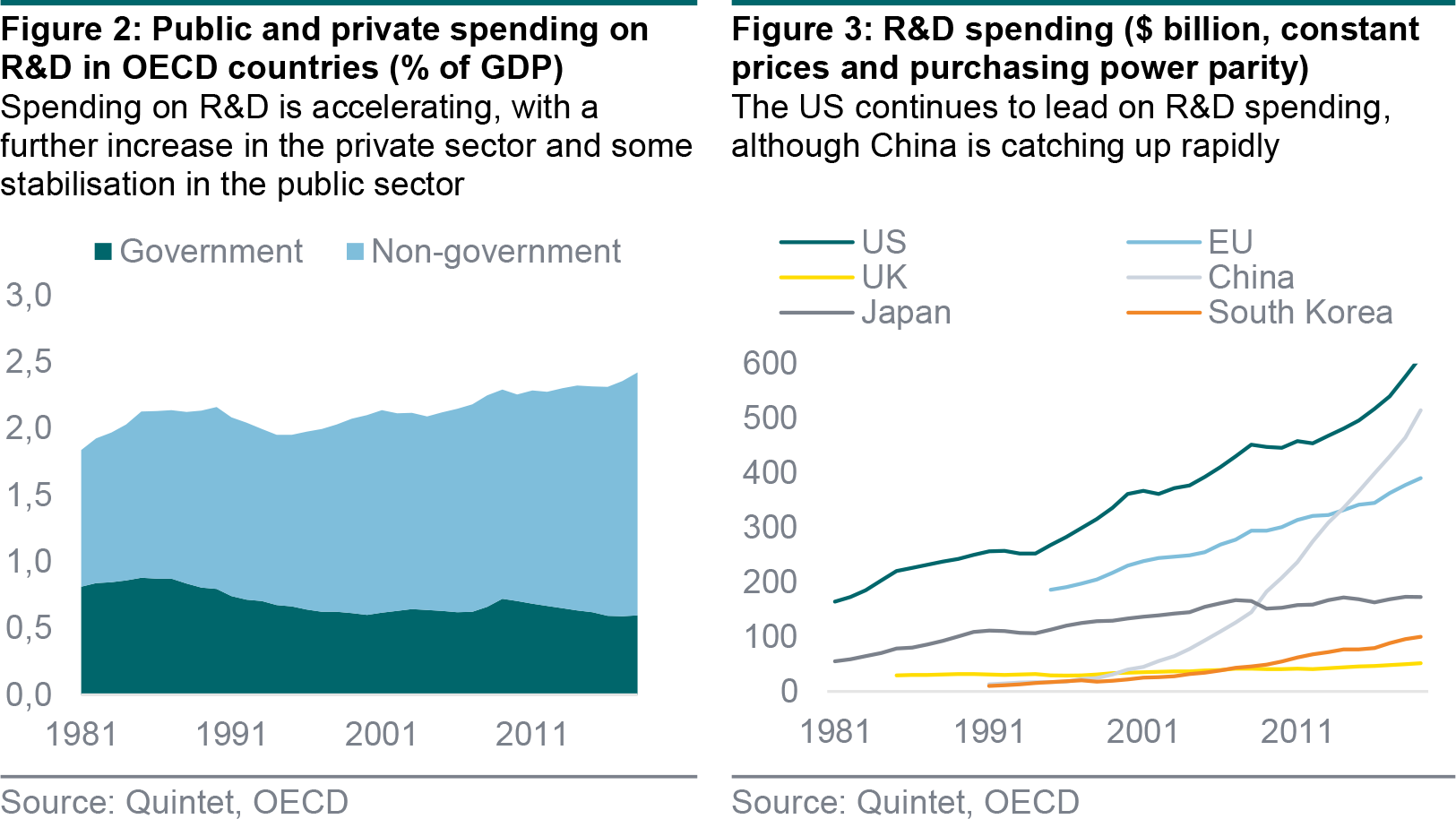

Spending on R&D as a share of GDP has been rising since the mid-1990s – mostly due to the increased role of the private sector. More recent, less comparable information shows a further pickup in private-sector spending. What’s new is that public spending on R&D, which has contracted for years, is now showing signs of stabilisation across many countries.

The success of the ‘messenger RNA’ approach behind the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines, and of bespoke antibody treatments, shows how science continues to transform medicine and genetics. Artificial intelligence is finally displaying significant progress in a range of promising fields, from predicting the shapes of proteins to natural-language recognition and driverless vehicles.

One view is that the age of ‘great inventions’ – things like the internal-combustion engine, electrification, plumbing and the like – is behind us. Any further step is likely to be more incremental: moving from the internal-combustion engine to electric motors in order to drive vehicles is one thing; moving from the horse to the car is another. We don’t believe this view explains productivity trends very well. It’s true that overall growth and productivity lag R&D outlays by quite a while. However, it’s also true that accelerating R&D during the 1980s and from the mind-1990s coincided with faster productivity. The only exception is the most recent decade, which has been characterised by several crises. However, over the past five years, on average, the trend points upwards.

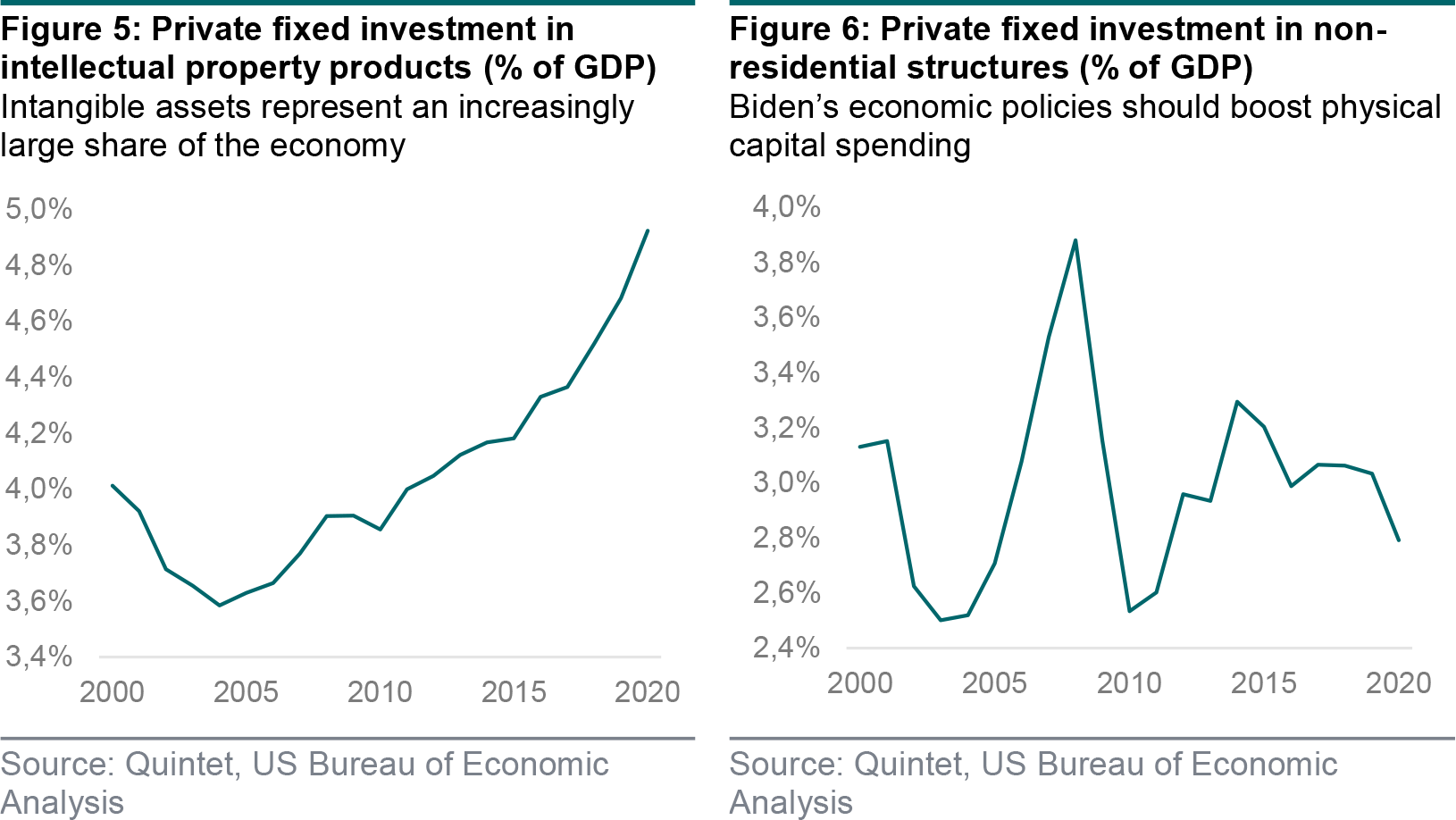

In the US, investment in intellectual property products amounts to about 5% of GDP. Investment in software has nearly doubled as a share of the overall economy over the past dozen years. Investment in computers and peripheral equipment jumped to a fresh record lately. As a result, non-residential investment is hitting new highs, which is all the more impressive as investment in structures – things like shopping malls, commercial property, hotels, hospitals and airports – has declined for quite a while. The important thing, though, is that even investment in structures looks set to rise from here, courtesy of US President Joe Biden’s $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan. Although how many shovel- ready projects are out there isn’t clear, over time we think investment should gain momentum.

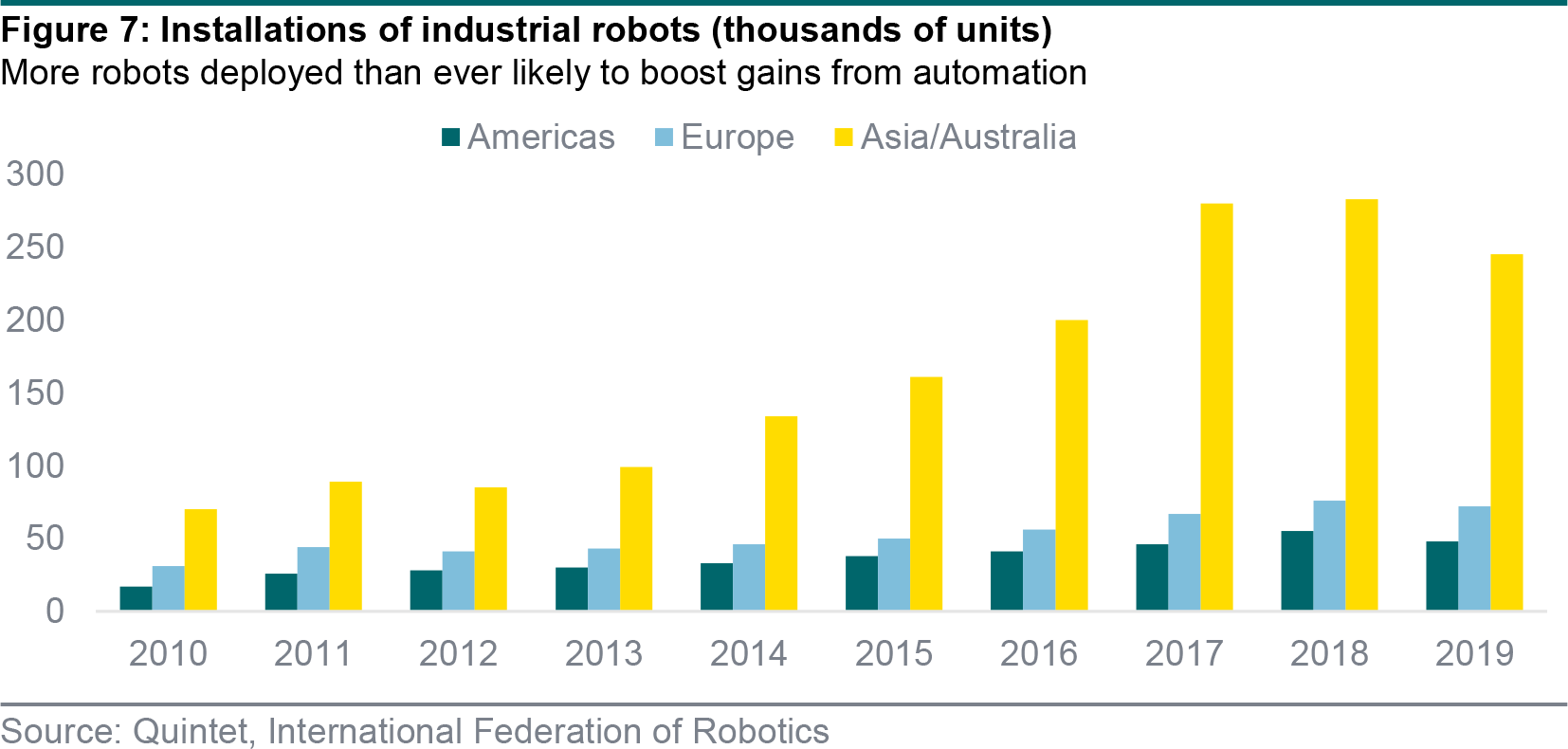

Crucially, this greater capital accumulation – physical and digital – is likely to boost industrial automation even further. Robotics is spreading not just in factories, but also in warehouses. Global orders for Japanese industrial robots are spiking, with China now the largest market. While most datasets pre-date the pandemic, which is likely to have distorted the 2020 numbers, the longer-term trend is one where robots, partly or fully, are involved in almost everything that’s produced and consumed. The pandemic has accelerated a number of pre-existing trends, from workers connecting through videoconferencing and consumers shifting to e-commerce to the adoption of digital payments, telemedicine, the ‘internet of things’, and the sharing and circular economy.

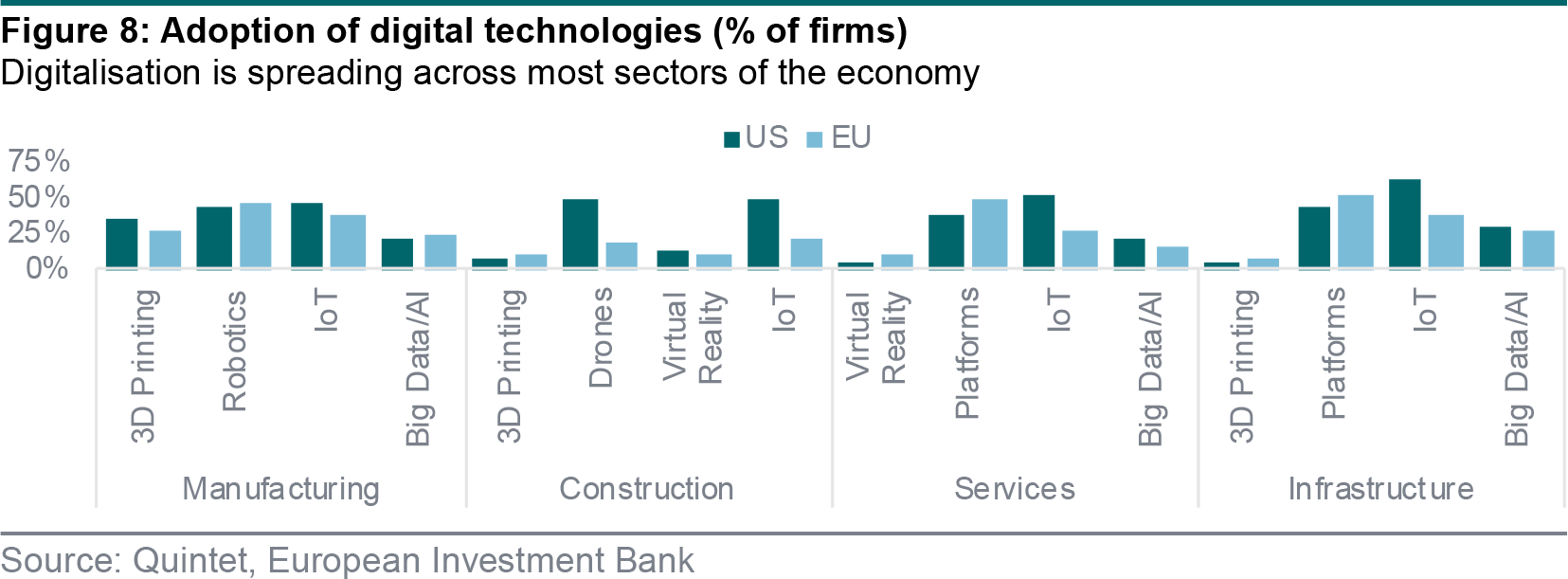

The digital economy encapsulates more and more things, from e-commerce and digital services to computer hardware and software – all driven by increased connectivity. Internet adoption rates continue to rise across the world and more people have access to a smartphone than ever before. The pandemic has changed the way we think about digital technology, how big it could become and how quickly it could get there. Growth of the digital economy means that consumers around the world can have access to jobs, goods, services, education, healthcare, entertainment and more – regardless of their physical location. Several technologies, from 3D printing and robotics to the ‘internet of things’ and big data/artificial intelligence, are spreading across geographies and sectors.

It looks as if faster adoption of digital technologies is boosting employment growth especially for workers with cognitive non-routine tasks – such as those employed by knowledge-based firms. Job creation looks moderate for those with manual non-routine ones, such as a range of services. And it’s slow for workers engaged in routine manual and cognitive activities in production and clerical roles, as these jobs get automated. Estimates point to a shift from a world where factories, machinery and equipment are crucial to one where intangible assets such as ideas, information and brands matter to a greater extent. The national accounts (the stuff GDP is made of) underestimate these assets, which are especially important in the US, UK and some of the northern European countries, but also in some key emerging markets.

What are intangible assets and how should investors think about them? Two points are relevant here. First, intangible assets aren’t just about digitalisation and technology. It’s that too, but it really is about intellectual property, networks, design, marketing and advertising, relationships and many other things that aren’t included in the official statistics. Basically, statisticians simply don’t know how to accurately estimate many of these things and so they leave them out. Figure 11 shows a classification by the European Investment Bank, along with what’s included in the macro statistics and what not. The variation in assumed capitalisation and depreciation rates reflects the unique nature of each type of intangible investment. For example, advertising has a shorter life than software.

The second point is a broader one. The key structural trends highlighted in this report mean that, in today’s service-led economies, what makes companies valuable isn’t their ownership of physical assets. Rather, the value increasingly is in intangibles: assets you can’t touch and see, but of huge value because they’re what makes a company unique. Take a smartphone. Its value is mostly in its software and multi-media applications, not in its production, as this is done by contractors assembling components made by third-party suppliers worldwide. Markets are volatile as investors constantly re-evaluate the price of an asset versus its intrinsic value. The price of a stock shifts up and down depending on greed and fear. Its intrinsic value comes from the firm’s earnings power.

This approach relies mainly on company accounts: valuation is based on a multiple of future profits and the book value of the firm’s assets. Of course, profits are revenues minus costs. If a chunk of costs is not current expenses like electricity or rent, but spending on intangibles that will generate future cash flows – such as advertising or R&D – then earnings and book value may both be understated. Intangibles can be used repeatedly and are often characterised by network effects: the more people use a firm’s services, the more useful and cheaper they become to other customers. This is why industries become dominated by a small number of big players.

But intangibles tend to generate bigger synergies than tangible assets more generally: with increasing economies of scale, a firm that rises quickly will often keep on rising, as ideas multiply in value when they are combined with each other. Figure 12 shows how the way of doings things (the ‘paradigm’) is changing across sectors. One way or another, this has to do with technological innovation first and foremost, but the concept is broader than that and has to do with the rising importance of intangibles, a greater use of digitalisation and automation, and organisational innovation. While quantifying any boost to economy-wide productivity, inflation and ‘equilibrium’ interest rates is rather difficult, the opportunities this generates at the sector and company level are clearer.

Authors:

Daniele Antonucci Chief Economist & Macro Strategist

Jonathan Chitty Senior Investment Analyst

Bill Street Group Chief Investment Officer

This document has been prepared by Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. The statements and views expressed in this document – based upon information from sources believed to be reliable – are those of Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. as of 17 May 2021, and are subject to change. This document is of a general nature and does not constitute legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. All investors should keep in mind that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that the value of investments may go up or down. Changes in exchange rates may also cause the value of underlying investments to go up or down.

Copyright © Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. 2021. All rights reserved.