Large-scale policy support and prospects of a vaccine breakthrough suggest default rates will peak at lower levels.

We’re positive on riskier credit markets with overweight allocations to euro high yield and emerging market sovereign hard currency bonds.

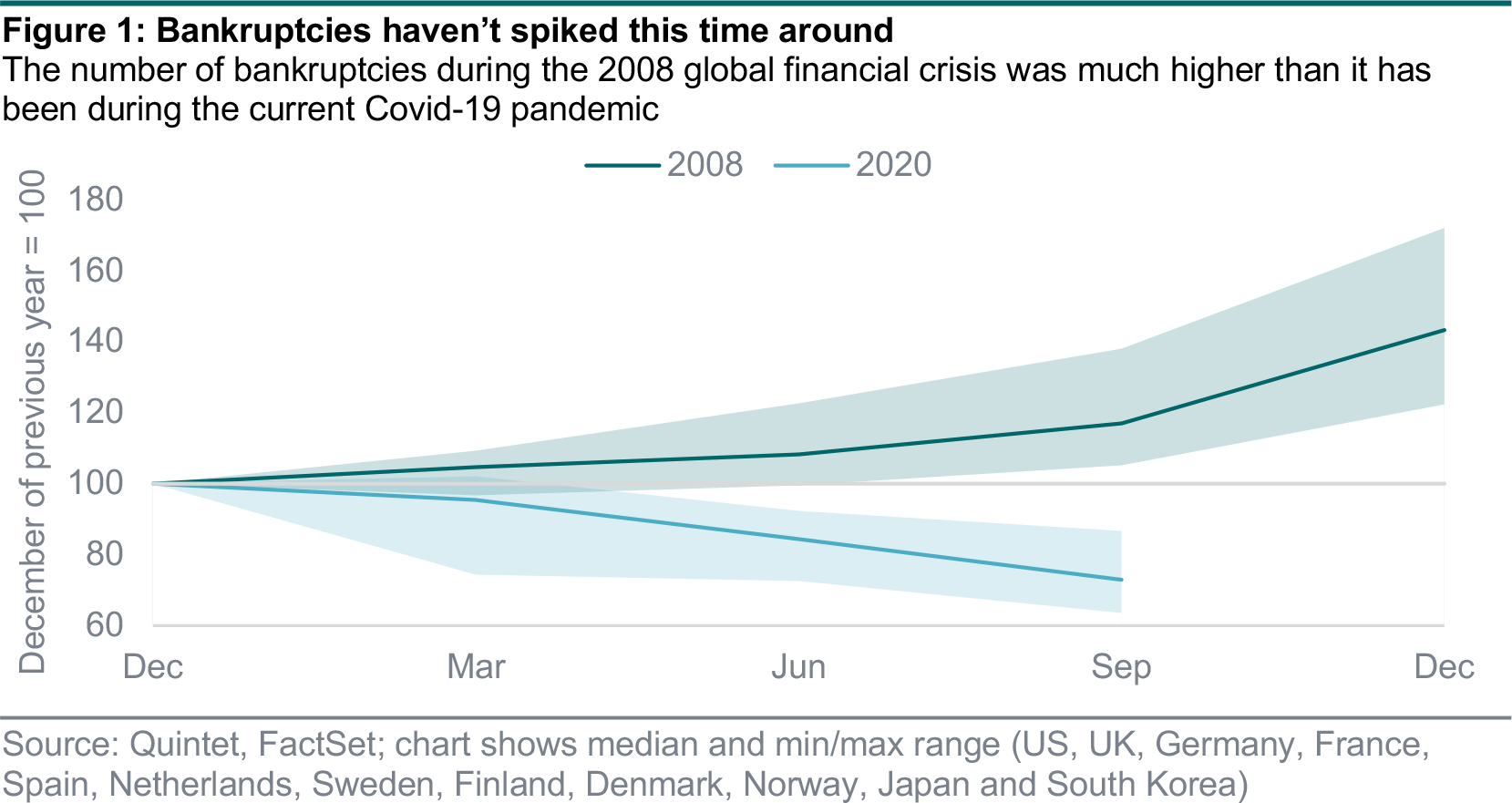

Covid-19 has made the largest hole in global GDP in nearly a century. However, the number of bankruptcies has remained surprisingly low so far. Relative to the start of the year, we're actually down. In contrast, the global financial crisis over a decade ago saw a rapid rise.

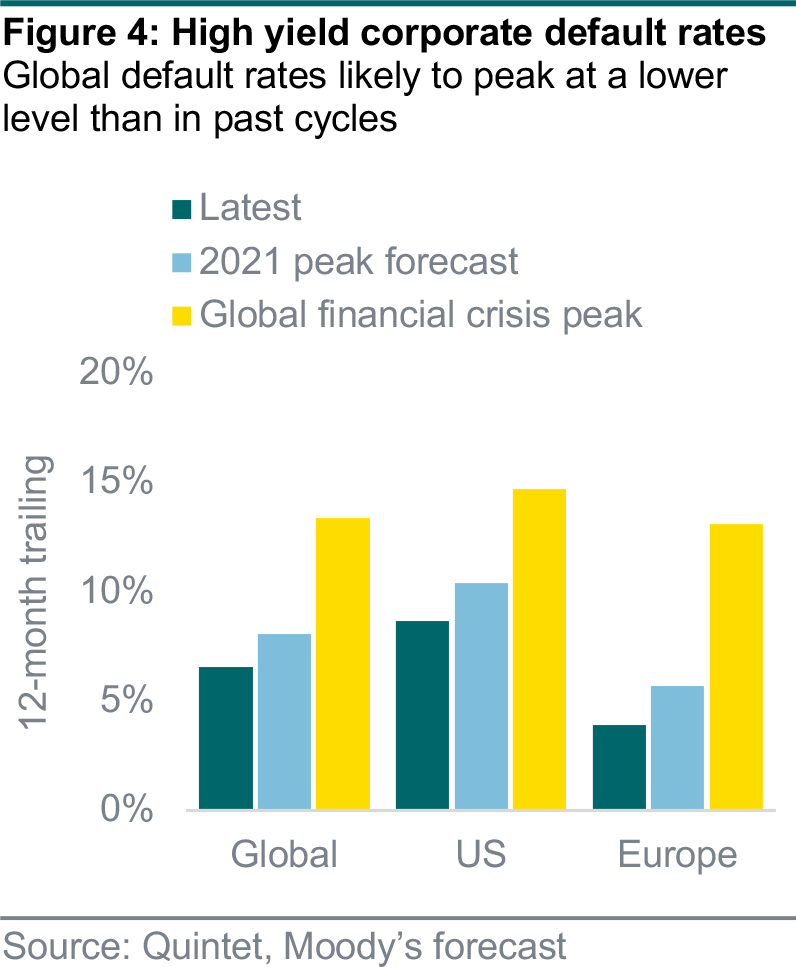

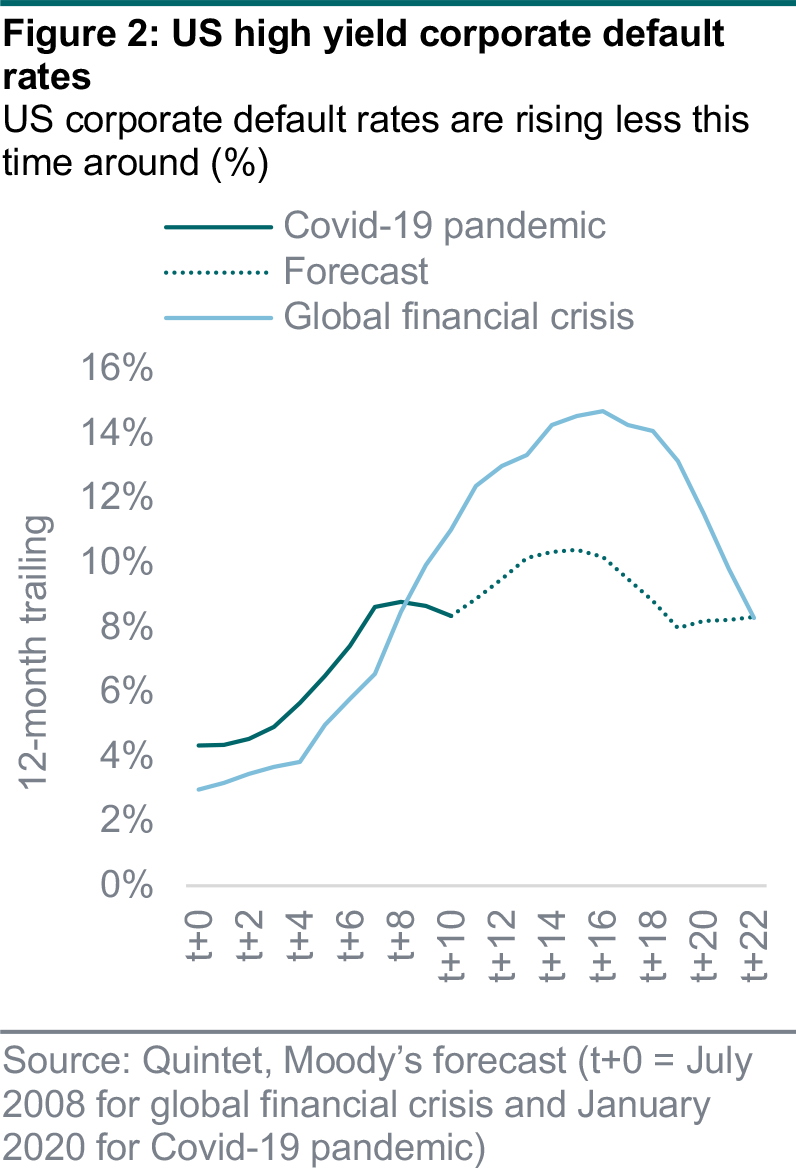

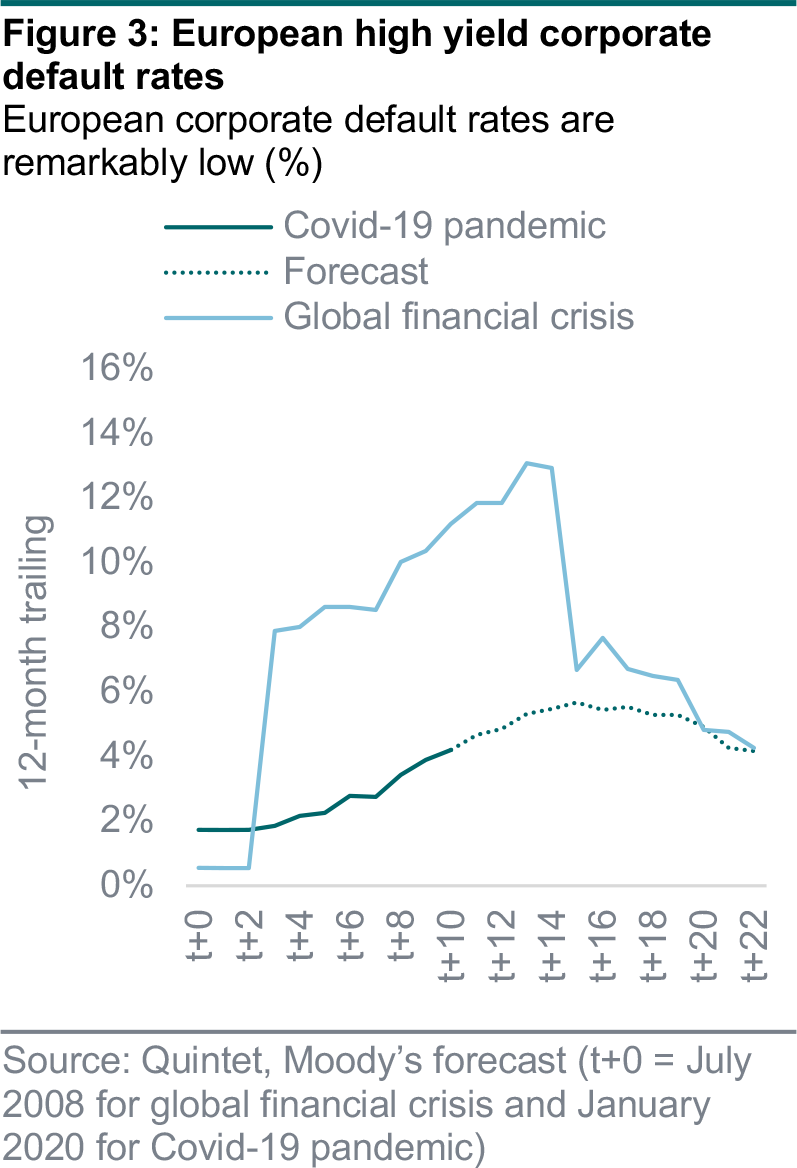

High yield corporate default rates are rising but they're nowhere close to the levels of 2008- 09, especially in Europe (accounting for a similar starting point relative to the timing of the shock). Specialised forecasts predict a further rise, but also a likely lower peak.

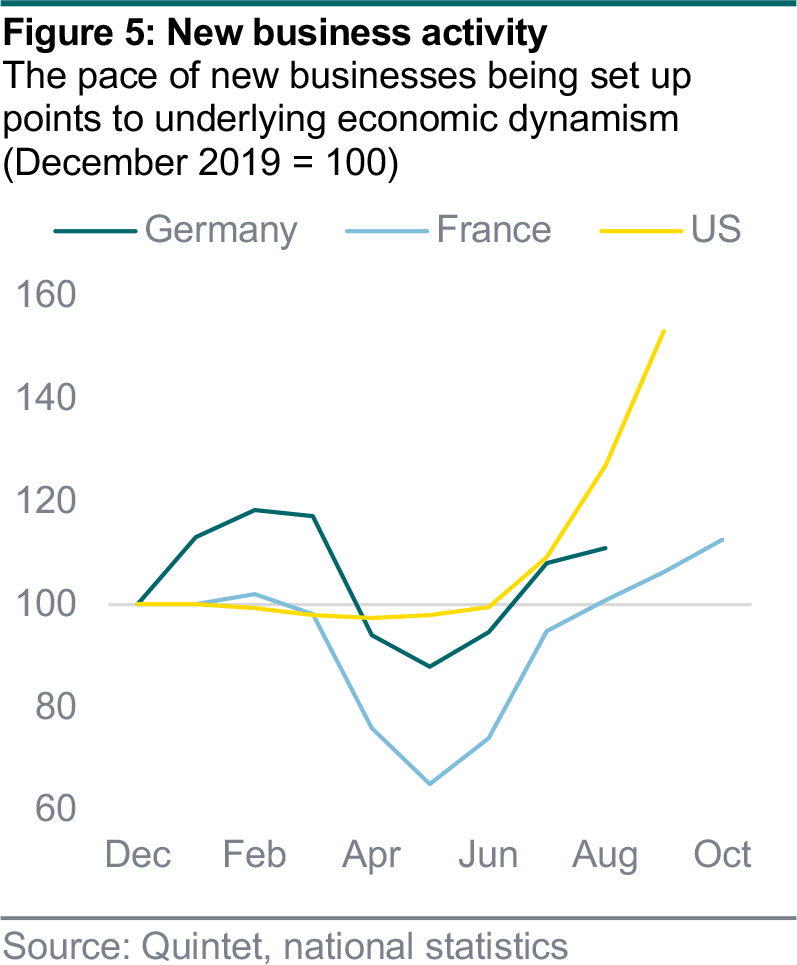

Perhaps surprisingly, new business formation is increasing in Germany and France, though moderately, and it's picking up significantly in the US. This may indicate that the economy isn't structurally impaired. If anything, the data show a remarkable resilience.

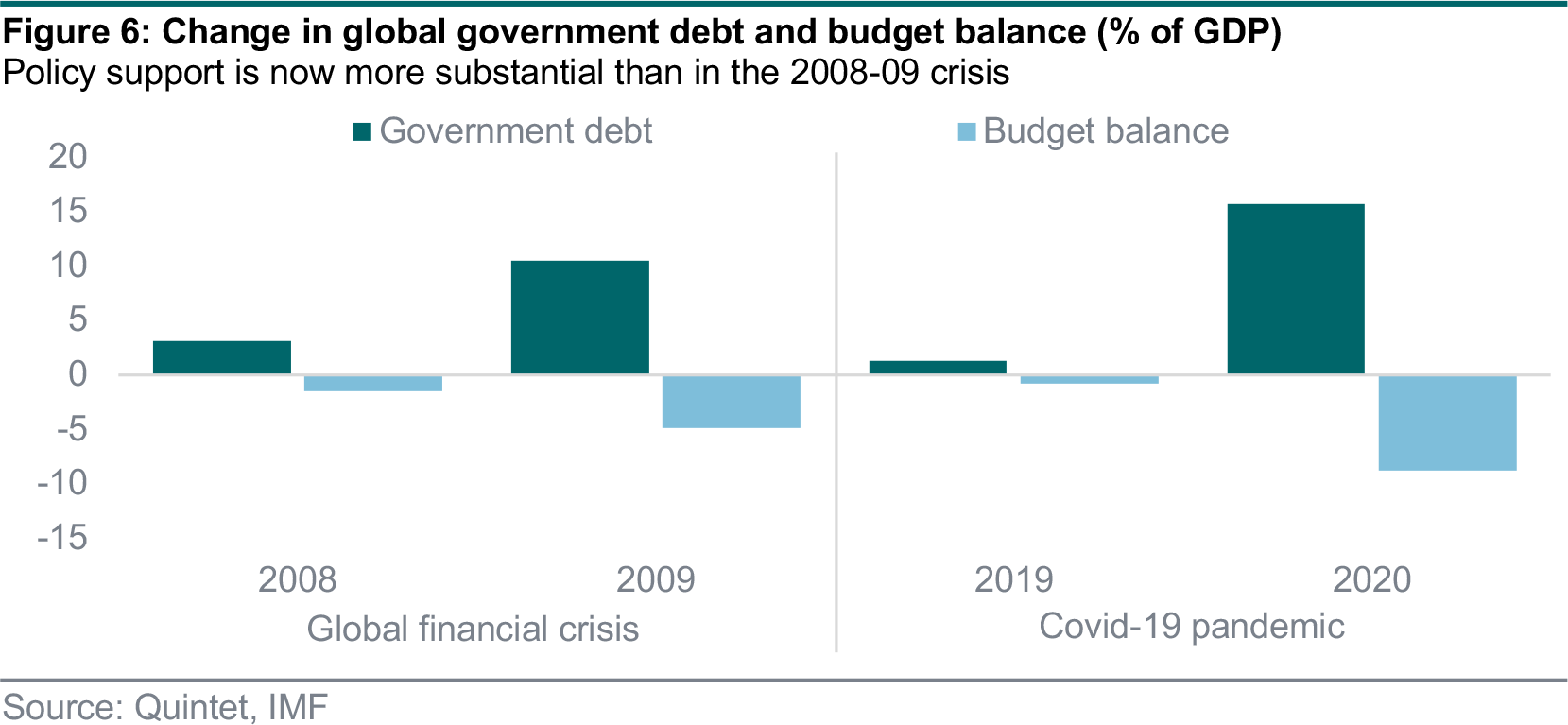

This milder default cycle has to do first and foremost with governments being able to borrow at affordable rates and spend vast sums, as central banks ensure cheap funding. A safe and effective vaccine soon should allow wider reopening and, therefore, mitigate credit stresses.

Earlier this month we dialled up the risk in portfolios by overweighting US equities against US investment grade bonds. We've also maintained our credit overweight, with a preference for euro high yield and emerging market sovereign hard currency bonds.

Much has been said and written about the impact of the pandemic on the economic cycle. The focus, understandably, has tended to be on the near-term effects on aggregate demand. Less explored are the longer-term effects on the supply-side of the economy. Should the markets worry about bankruptcies acting as a drag on economic recovery and negatively impacting the credit markets? Turns out, bankruptcies have not spiked this time around (figure 1) – a key difference with the 2008 crisis.

That is primarily because central banks have kept the liquidity taps wide open to mitigate credit impairment, while ensuring cheap funding for governments to provide large-scale fiscal stimulus. Unless expectations of an imminently available safe and effective vaccine prove wrong – if, for example, the approval process is extended or efficacy does not meet expectations – we believe that bankruptcies should remain below the level witnessed during earlier recessions.

Corporate default rates haven’t risen as much as during the global financial crisis over a decade ago. This can be seen by comparing their trajectories, starting in July 2008 (two months before the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers) and January 2020 (two months before the lockdowns this past spring). The difference looks particularly stark in Europe, while in the US the trend didn’t seem particularly different initially, though it now appears to be the case there too. Forecasts provided by Moody’s – one of the major credit rating agencies – suggest further increases in the months ahead, but a peak well below that of the global financial crisis (figures 2, 3 and 4).

Another way of saying this is that the distressed sectors are likely to recover more swiftly this time around, and leave the economy less structurally impaired than the magnitude of the Covid-19 shock would suggest. Importantly, while information isn’t fully comparable and data availability is more limited, it appears that new business formation is rising moderately in Europe and surging in the US (figure 5). This may point to the kind of underlying dynamism that will prove a shot in the arm for the global economy in the months to come.

One key assumption underlying our forecast is that governments in countries hard-hit by the virus will continue to do all they can to replace private-sector income lost to the lockdown disruptions via substantial wage subsidies, unemployment benefits and other fiscal transfers. While this will contribute to even higher debt, we believe that governments can afford to spend heavily as central banks will likely continue to anchor funding costs at rock bottom (figure 6).

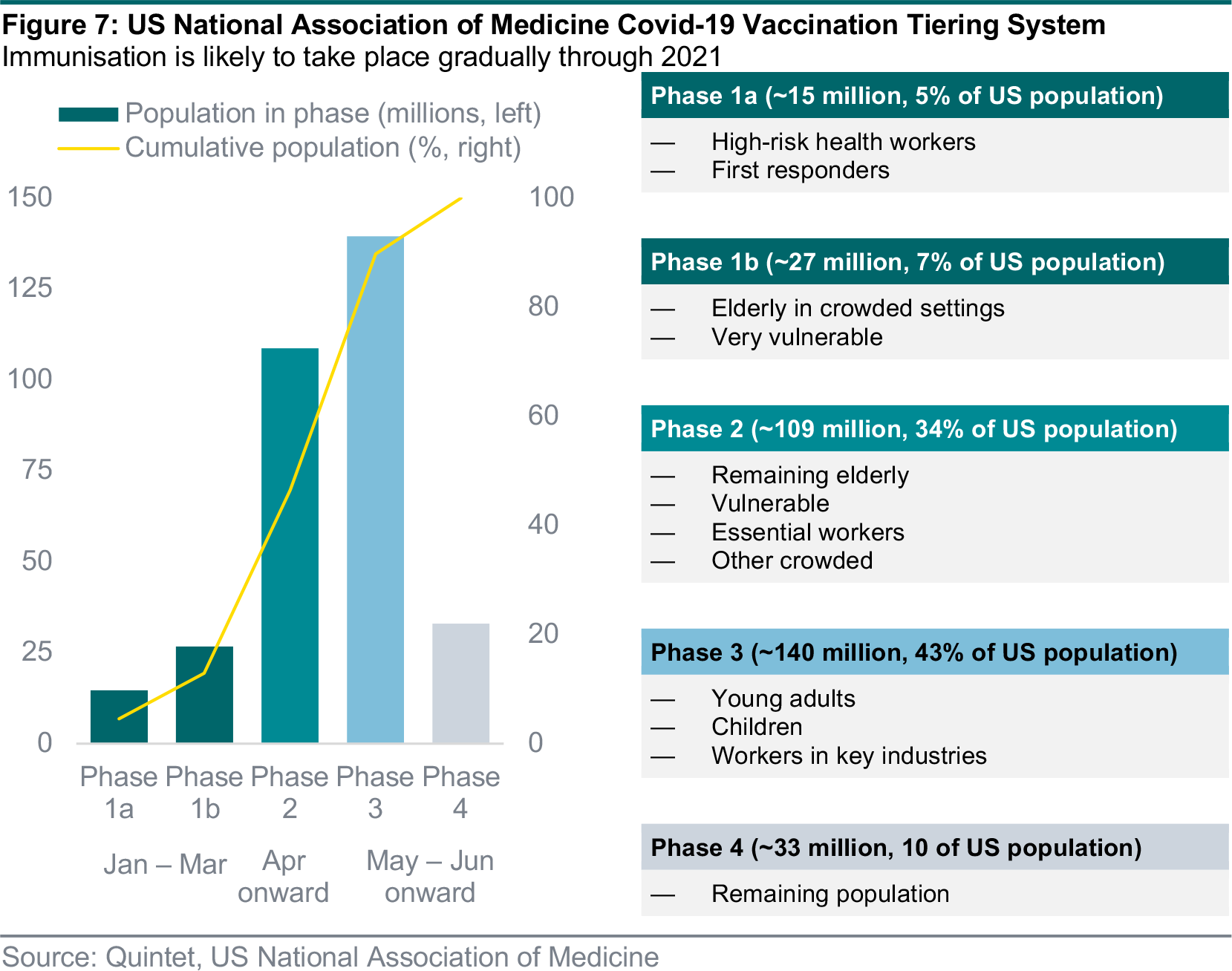

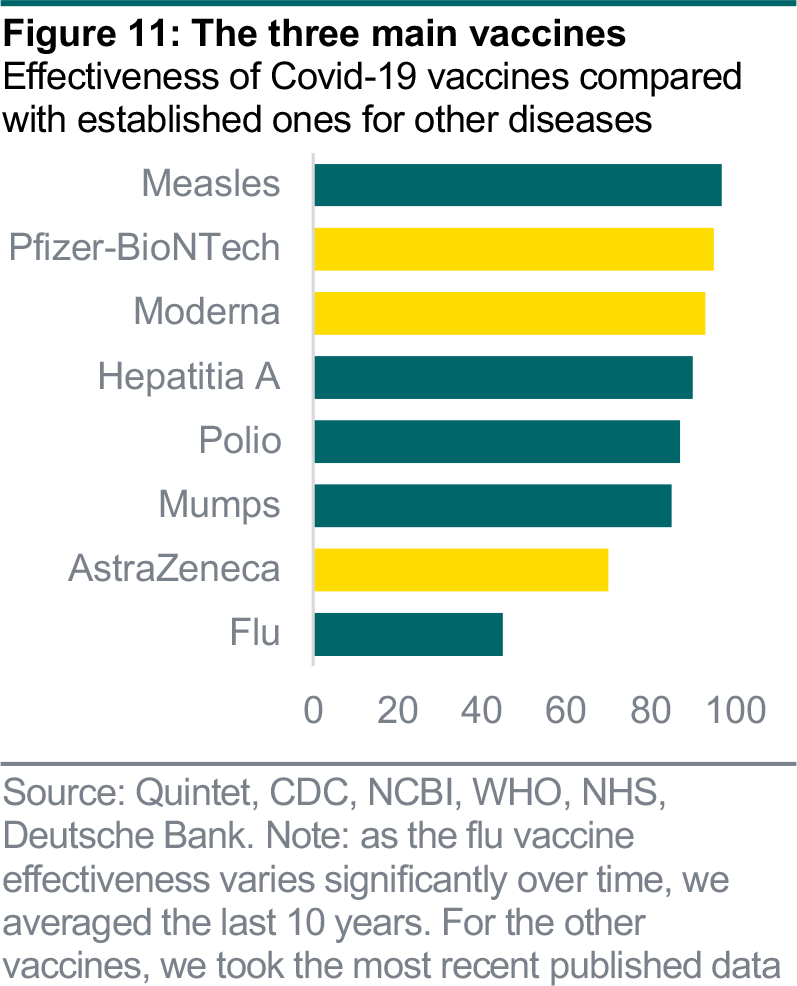

More crucially, our base case envisages a medical breakthrough at the turn of the year. Following preliminary announcements that the Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna and AstraZeneca/University of Oxford candidate vaccines have high efficacy rates, one or more approved vaccines by January now looks increasingly likely. This should be followed by rapid immunisation of high-risk groups, ranging from the elderly and those with serious health issues to healthcare workers. Broader distribution might then start as early as the second quarter of 2021.

As the population builds immunity – and assuming that policy easing continues – the restrictions are likely to be relaxed and, eventually, lifted altogether. Therefore, activity should rebound this coming spring, and much more quickly relative to previous recessions that were triggered by policy tightening and/or balance-sheet repair. We’ve seen these dynamics play out in the third quarter of this year, following economic reopening.

We’re aware that uncertainty still exists about the complex logistics of manufacturing, transporting and delivering the vaccine worldwide. This is why was assume that the immunisation process is going to be gradual, which is also consistent with the tiering system suggested by the US National Association of Medicine (figure 7). That said, while we assume that mass immunisation is only likely to come over time, we think that the process could be accelerated by linking the reopening, or greater consumption of certain services – air travel, for example – to getting a vaccine.

In late November we dialled up our allocation to risk in portfolios by overweighting US equities against US investment grade bonds on the back of improving economic conditions and our positive outlook for 2021. We’ve also maintained our overweight allocation to credit, with a preference for euro high yield and emerging market sovereign hard currency bonds:

- Overweight euro high yield bonds (hedged). Credit spreads have come down towards their long-term average, but yield carry over investment grade remains attractive. Defaults should be kept in check by the recovery we expect as well as by policy support.

- Overweight emerging market sovereign hard currency bonds (hedged). Spreads have compressed notably, but carry remains attractive at current levels. We see room for further spread tightening in the high yield segment, which accounts for 44% of the index.

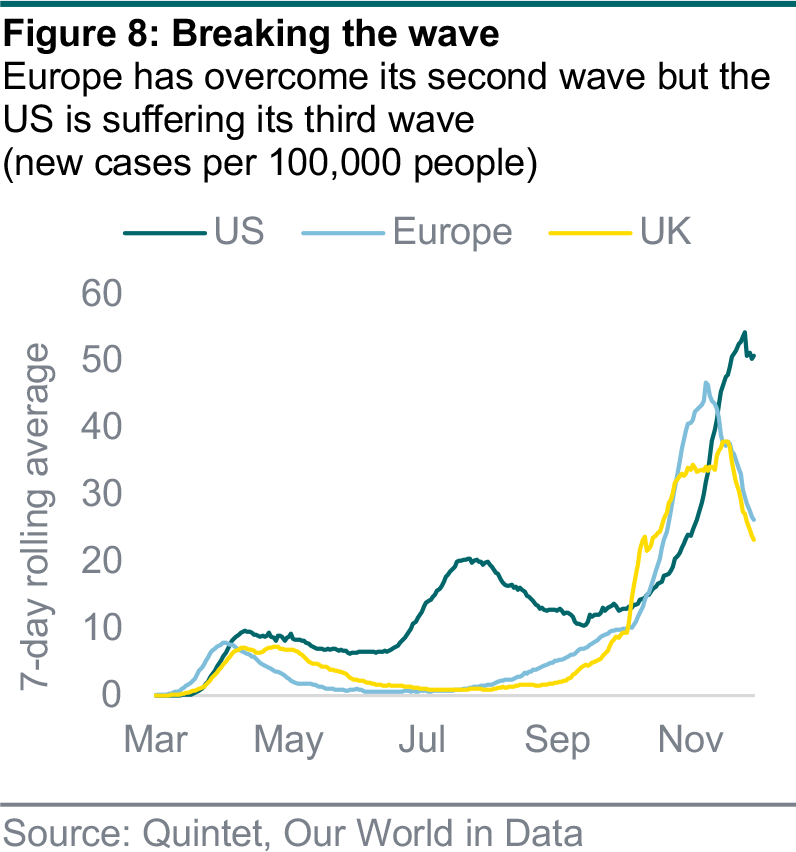

Globally confirmed cases have approached 63 million, and there have been more than 1.4 million fatalities. Regional trends differ, not least due to different lockdown approaches and starting points. Within Europe’s second wave, new infection trends in France and Spain have been slowing over the past few weeks. Italy’s infection curve seems only slightly behind the peak and Germany’s is still trending sideways, albeit at a lower level. As a consequence, while France has announced first plans to scale back some restrictions in the upcoming weeks, Germany has prolonged its measures with limited easing from Christmas to January 1. In the UK, the current lockdown will end on December 2 and is being replaced by a return to the system of three tiers across the regions, which is likely to remain in place until early 2021. The good news is that the seven-day average of new Covid-19 cases in the five major European countries has fallen by almost a fifth in one week, which is the fastest weekly decline in more than five months.

The EU and the UK have overcome their second waves (figure 8), but the US is still facing a rising third one, although with signs of flattening. The seven-day US average of new cases has reached a new 173,000 high – however, when adjusted for the increase in testing, the weekly growth rate has slowed significantly. Among the 10 states with the highest new cases, only three have seen growing numbers ahead of testing in the past week. States and cities have taken significant measures, including school closures in New York City and California’s 10pm to 5am curfew – although Florida’s governor has ruled out a further lockdown. Overall, the measures should help the US overcome its third wave over the next several weeks.

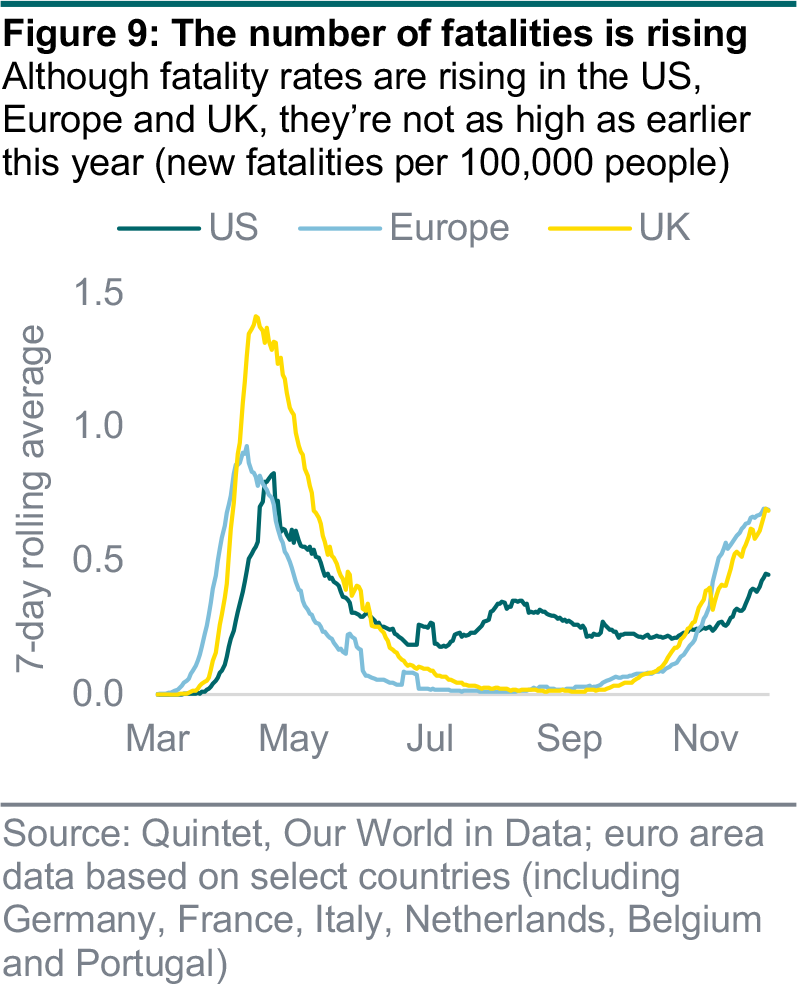

In Europe and the US, hospitalisation and fatality rates are still rising (figure 9). However, these trends are slowing. Hospitalisation rates have stabilised in countries where they were especially high, such as Belgium and the Netherlands, while the number of people in intensive care is no longer increasing as drastically as before in other countries. This trend indicates that overall measures were taken in time to avoid overburdening most health systems. European and US fatalities per day remain significantly below the levels in the first wave in spring.

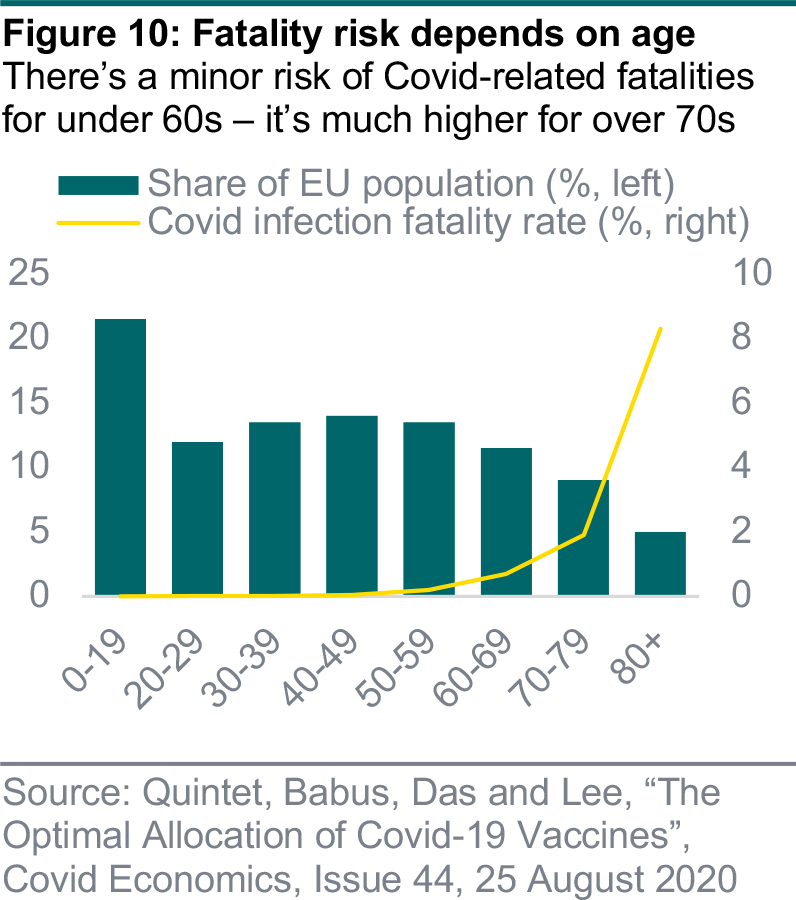

When it comes to the risk of dying from Covid-19, it’s still important to consider the risk by age. Based on figures for the EU, the risk is low for people younger than 50 (figure 10), and only starts to rise significantly for people over the age of 70. The low fatality risk for people of working age is an important point to consider when assessing the economic impacts of the virus.

The end of the crisis is now in sight, with several vaccines being developed – AstraZeneca’s latest announcement added to positive news from Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna. Even if the AstraZeneca vaccine is less effective than the two other candidates, it’s easier to store and its 70% effectiveness makes it an important part of the upcoming immunisation process. As these vaccines should probably be approved before year-end by the FDA and European authorities, vaccination could start as early as December, raising hopes that herd immunisation could be reached in most parts of the industrialised world already around summer next year.

While herd immunity will likely be important to remove all restrictions, a further moderation of the current virus waves should enable governments on both sides of the Atlantic to remove restrictions gradually in the weeks and months ahead. Economic activity is slowing, but less sharply than in the spring. Businesses and people have adapted, and many parts of our economy have stayed open (including schools, factories and construction sites), which is limiting the impact.

However, after the surprisingly strong bounce in the third quarter, we expect GDP in the last three months of 2020 and early 2021 to weaken, particularly in Europe, before economic recovery begins to gather pace in the spring. As a consequence, while slightly increasing our GDP forecasts for 2020 in the light of the strong summer rebound, we recently moderated our 2021 forecasts slightly – to 4.5% growth for the euro area next year following a contraction of 8% this year. For the US, we expect a 3.8% contraction this year followed by ~4% growth next year.

Authors:

Daniele Antonucci Chief Economist & Macro Strategist

Carolina Moura-Alves Group Head of Asset Allocation

Bill Street Group Chief Investment Officer

This document has been prepared by Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. The statements and views expressed in this document – based upon information from sources believed to be reliable – are those of Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. as of November 30, 2020, and are subject to change. This document is of a general nature and does not constitute legal, accounting, tax or investment advice. All investors should keep in mind that past performance is no indication of future performance, and that the value of investments may go up or down. Changes in exchange rates may also cause the value of underlying investments to go up or down.

Copyright © Quintet Private Bank (Europe) S.A. 2020. All rights reserved